To confer importance: John Ban MacKenzie

December 31, 2020 on 2:01 pm by Michael Grey | In Photographs, Random Thoughts, Stories | Comments Off on To confer importance: John Ban MacKenzieThanks to technology we’re all photographers. The mobile phone-cum-camera is everywhere. The late writer, Susan Sontag, famously wrote of the subject in her book On Photography (1977). I’ve talked about some of her ideas before but her cleverness stands repeating. She wrote that to photograph is to confer importance. I suppose importance is relative to the photographer and the person that observes the photographed subject. Your pic of your take-away boxed lunch of chicken tikka, pilau rice and Gulab Jamun is likely to mean much more to you than me. But, still, to be fair, a tasty lunch of colourful Indian treats has, for a time, an importance of sorts to any photographer and so there’s a ring – or, maybe, tinkle – of truth to Sontag’s words.

The sometimes mindless ease in which we today photograph pretty much anything is still, I think, a novelty; or, at least, a much-appreciated marvel of technology. It wasn’t that long ago that people had their cameras loaded with chemically treated plastic film and, so, a finite set of chances to capture any moment in time. Those “chances” usually had a 24 or 36 count: the usual number of exposures available on commercial film rolls. When your chances at capturing a moment are limited photographers then usually paused and considered before clicking the shutter (I use the word photographer in the most generic sense: think shaky-handed enthusiastic people: “Smile! Say cheese! Your eyes were closed, I have one more shot! Wait! The flash didn’t go off!”. I’m referring to this ilk of picture-taker.) But to those long before us even a Kodak Instamatic camera loaded with film would be sheer luxury.

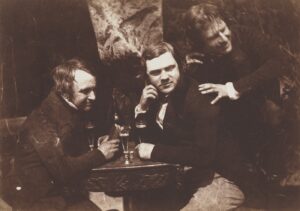

Consider David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, two of the world’s earliest photographers. Their’s was the first photography studio in Scotland – and among the first anywhere. In the 1840s they set about recording Scottish life and landscape eventually recording over 3000 images before the death of Adamson in 1848. They used the calotype process to capture images. Bright light was required and, so, many of their images were taken outdoors. The calotype procedure required exposure time of one to three minutes. The stillness required of subjects was often aided by clamps and supports. In spite of this hard-to-imagine reality their photos often suggest genuine spontaneity. The pub scene here, entitled “Edinburgh Ale”, shows (L-R) James Ballantine, Dr George Bell and David Octavius Hill. In the blurriness of Hill there’s a suggestion the man himself had trouble holding his smiling face for the duration of the long exposure. Still, a moment in time from almost two hundred years ago is fascinating.

One subject of Hill and Adamson’s photographic output was the superstar piper of his day, John Ban MacKenzie. Born in Achilty, near Contin, around 1796 he lived most of his 68 years as the personal piper to Mackenzie of Allangrange, Davidson of Tulloch and, for almost 30 years, the Marquis of Breadalbane. While he had a number of excellent tutors, including at least four winter seasons with John Mackay on the Isle of Raasay (father of Angus Mackay, Queen Victoria’s first piper and author of seminal printed books of pipe music) he was described by Seumas MacNeill in his Masters of Piping (2008) as the first great piper in history not to have been taught by the MacCrimmons. He was a great performer, prize-winner and teacher. Much of today’s piping connects to John Ban MacKenzie, through his extensive teaching including pupils Donald Cameron, Alexander MacDonald (father of John MacDonald of Inverness) and many others. According to Seumas MacNeill he was “the last of the old school, the complete piper; he could kill the sheep, make the bag, turn the pipes, cut the reeds, compose the tune and play it”. It was John Ban who composed one of my most-liked pieces of piobaireachd, “His Father’s Lament for Donald MacKenzie”, the lengthy and flowing melody made to help mark the death of his beloved son.

The late master, John D Burgess, remarked once that John Ban MacKenzie was a hero of his. I think knowing of a hero of a hero seriously underscores the radiant importance of that person. John Ban MacKenzie didn’t need a photo to have importance conferred. He was.

And yet we look to Hill and Adamson. They duly anointed John Ban MacKenzie with their version of cultural importance when around 1845 his visage was captured. John Ban: one of the first pipers in history to be photographed.

Thanks to Hill and Adamson’s studies we can today easily imagine that bright mid-19th century day in Scotland when John Ban MacKenzie stilled himself for the camera. Pipers will look to his hands, his pipes and where they’re tuning. His stylish high-cut Glengarry only adds to his reputed height of six feet four inches. He surely lived a good life with claret jug never far from the pipes – or so it appears.

Susan Sontag said, too, that all photographs are memento mori, a reminder of the inevitable. To take a photograph, she said, is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Sontag believed that in freezing the moment in time “all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt”.

So a nifty segue, maybe, to the (blessedly thankful) passing of a year and a hero’s hero, John Ban MacKenzie. And to two pioneering photographers who conferred importance on people and things that allow us today to have them better imagined.

Happy New Year when it comes your way!

M.

No Comments yet

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Dunaber is using WordPress customized and designed by Yoann Le Goff from A Eneb Productions.

Entries and comments

feeds.

Valid XHTML and CSS.

Entries and comments

feeds.

Valid XHTML and CSS.